- 05 Jan, 2021

- Topic of the Month

1. What Is “Phishing”?

The term “phishing” is defined in several ways. This topic may cause confusion not only because of its definition changes but also because it has different types (deceptive phishing, spear phishing, whaling, vishing, etc.).

In a broader sense, phishing is an attempt of swindlers (cybercriminals) to obtain personal information such as usernames, passwords, and credit card details.

A more accurate definition is found in the Phishing Activity Trends Report provided by APWG (Anti-Phishing Working Group): “Phishing is a crime employing both social engineering and technical subterfuge to steal consumers’ personal identity data and financial account credentials.”

And yes, do not think that phishing is merely a technical hocus-pocus: besides technical “literacy”, successful phishing requires skills to bamboozle and manipulate individuals.

While describing phishing, Sascha Rommelfangen from CIRCL even goes beyond this and explains: “The act of phishing is a social engineering attack and does not require any technical exploitation of vulnerabilities. Instead, it focuses on the human and their weaknesses, like inattentiveness, misinterpretation or mislead judgement caused by the influence of the attacker’s correspondence… The attacked person always voluntarily gives the requested information to the criminals.”

As per GovCert, phishing is defined as the “Use of fraudulent computer network technology to entice organisation’s users to divulge important information, such as obtaining users’ bank account details and credentials by deceptive e-mails or fraudulent website.”

Either way, phishing is a form of cybercrime, where attackers pose as a reputable entity to obtain information from their victims for using that information for financial gain. Regardless of how we define it, phishing is one of the most well-known and fastest-growing scams on the Internet today.

The aim of this article is to give you a general overview of this threat, its geographical prevalence, sectors affected, and ways you might fight against this type of cybercrime.

2. A bit of History and Name Origins

You might wonder why we use “ph” in place of “f” in the spelling of the term phishing. There is a good reason for that. Some of the earliest hackers were called “phreaks”. Phreaks and hackers have always been closely linked and the “ph” spelling is used to mark this connection.

The first time when the term “phishing” was used and recorded was on January 2, 1996. The first registered phishing scam was done on AOL (America Online) with the tool called AOHell that enabled hackers to steal passwords and credit card information among millions of AOL users causing significant damage.

In 2001, phishers turned their attention to online payment systems. Later, in 2003, phishers registered dozens of domains that looked like legitimate sites like eBay and PayPal and used e-mail worms to send out spoofed e-mails to PayPal and eBay customers. Those customers were led to spoofed sites and asked to update their credit card details and other identifying information.

Since 2004, phishing attacks have been targeted banking sites and their customers…

2.1. How Did We Get Here?

Unlike the good old days, when breaking into a bank involved shooting into the air from horseback, digging tunnels, or bribing the local safecracker to join the roadblock gang to rob a bank, the methods used, the extent of the damage caused, and the geographical range of such crime significantly changed.

Nowadays, cyber-thieves can do much more harm remotely with much less risk: their activity remains undiscovered or even unnoticed for most of the time. And yes, they do not need to organise getaway cars, get explosives nor do they wear balaclavas…

Similarly, these days you would not normally hear the shouting, “Hands up, this is a bank robbery!” The chance is much higher though that you would receive an innocuous-looking e-mail that asks you to “reset your password”.

Also, the malicious codes of cybercriminals work for them 24/7 without the need for constant supervision. These “silent robbers” are among us, and we must always stay vigilant unless we want to hit the mark of our money with a stick.

“Classic phishing attacks, which were spotted miles away because they were riddled with grammatical or spelling nonsense, is a thing of the past,” said Thomas Koch, Associate Partner and Cybersecurity Leader at EY Luxembourg, on a cybersecurity conference during the Cybersecurity Week Luxembourg, 2019.

3. What is the difference between smishing, vishing, and whaling?

These are all different ways of the so-called social engineering (manipulating victims by scammers into doing what they want). There is a difference between them in terms of who the target is, how the attack is implemented (via mail, phone, SMS).

Smishing (a combination of the words SMS and phishing) is the attempt by scammers to acquire personal, financial or security information by text message. Sometimes these attackers try to get victims on the phone by sending a text message asking them to call a number, in order to persuade them further.

Vishing is phishing over the phone where scammers try to persuade their victims to share information by posing as bank staff or other financial service employees. It is social engineering by telephone: these scammers usually make the call with the aim of gathering personal and confidential information.

Whaling (also known as CEO fraud or spear-phishing) uses methods such as email and website spoofing to trick the victim into performing specific actions, such as revealing sensitive data or transferring money. Here, the target is a senior or influential person at an organisation.

4. Protect and Prevent from Phishing

4.1. How Does Phishing Work?

- Under no circumstances share your login credentials with anyone.

- Only use your login on the official app, never download the application from anywhere else.

- Copy and paste URLs from e-mails and check them before visiting.

- Most importantly, do not click on a link if you received an e-mail that asks you to perform an action that you did not initiate (reset password, validate your account…).

- Always check a link before clicking on it. Hover your mouse over it to preview the URL, and look carefully for misspelling or other irregularities.

- Always make transactions on secure websites. If you cannot see the green lock icon in the browser’s address bar or see the “https” prefix before the site’s URL, it is very likely that the site is not secure.

- Use 3D Secure to make your online transactions more secure.

Phishing is usually done over e-mail, instant messaging, or phone. The attack normally works by creating a false feeling of security: the information appears to be legitimate and comes from a reputable source (state institutions, well-known companies, banks, etc.). The whole point of phishing is to fool you into giving away your personal information so the swindler can somehow use that information for their financial benefit.

The attackers create fake websites, e-mails, and text messages containing malicious links or attachments. People are lured to share confidential information when opening the attachment or clicking on the link. The information gained by attackers is then used for identity fraud, but could also lead to the execution of fake bank transactions.

One of the techniques used is to indicate that, due to problems (such as a database update, a problem occurred with a server, security/identity theft concerns, etc.), the recipient is required to update personal data such as passwords, bank account information, and so on. Also, the message includes warning that failure to immediately provide the updated information will result in suspension or termination of the account.

It is also important to understand that phishing is in very close connection with human psyche: every time a regional or global crisis erupts, the number of phishing scams increases. Also, the topic of the phishing campaign changes: “COVID-19”, “face mask”, “Black Lives Matter” … just to mention some of the most recent ones.

The topic of the phishing campaign should not need to be related to a crisis, though, it can relate to one of the followings, too:

- Impersonating trusted brands (PayPal, Facebook, Microsoft, etc.)

- Tempting target individuals with too-good-to-be-true offers

- Exploiting people’s eagerness about the latest news, trends, celebrities, etc.

- Phishing can also have political motivation: in 2016, the Democrat campaign was hacked during the presidential campaign in the USA.

Phishing is a social engineering attack and so uses opportunities to establish a trust relationship with the victim. Fear is a good transport medium, stressing to lose access to the mail or bank account is usually a common way to perform an attack. In general, any kind of important event can cause an increase of phishing using such a dedicated theme, for instance, the Olympic games or environmental disasters.

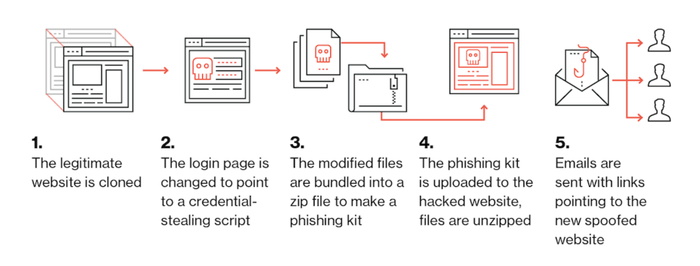

4.2. The Anatomy of a Phishing Kit

A phishing kit is a collection of tools that makes it easier for cybercriminals to launch their phishing scams even with little or no technical skills. The kit bundles web components of phishing attacks and tools that need to be installed on a server. Once installed, the only thing the phishers need to do is to send out e-mails to their potential victims by using a mailing list.

Here is the process of how it works visualised by Duo Security:

4.3. How do you protect yourself from phishing?

- 94% of malware is delivered via e-mail.

- Phishing attacks account for more than 80% of reported security incidents.

- $17,700 is lost every minute due to phishing attacks.

- 60% of breaches involved vulnerabilities for which a patch was available but not applied.

- Attacks on IoT devices tripled in the first half of 2019.

- Data breaches cost enterprises an average of $3.92 million.

Phishing has been discussed thoroughly in this article, only one question remained unanswered: How can we avoid biting in a phisher’s hook?

3D Secure is an additional security layer for online credit and debit card transactions: besides the “good old” ID and password combination, your bank sends you an instant message just before you would make the online transaction making it nearly impossible for the hackers to abuse your personal and card data.

But again, always stay vigilant and follow the propositions listed above. There is no “bullet-proof” solution: as long as a human individual is involved, there will always be victims of phishing scams.

Paperjam has reported recently a phishing scam which “…has enabled fraudsters to pocket more than 20,000 euros using credit cards from customers who have communicated their bank details”.

5. Why is Phishing So Important?

To demonstrate this, read below some global cybersecurity statistics for 2020 from the CSO Digital Magazine.

Although ransomware is the most difficult to solve (it is basically impossible to cure the damage if you do not have a usable backup) and maybe the most expensive type of cyberattack, phishing is still the most widely used. As per Symbol Security, phishing is the most common cyberattack followed by spear phishing, smishing and vishing.

6. Phishing Is a Worldwide Problem

We can learn from a BitSentinel article that phishing is a very serious problem on a global scale:

- 32% of confirmed data breaches involved phishing.

- 37.9% of untrained users fail phishing tests.

- 26 billion lost globally to business e-mail compromise crimes between June 2016 and July 2019 with over 1.7 billion in 2019 alone.

- Puerto Rico’s government lost $2.6 Million in a single phishing attack.

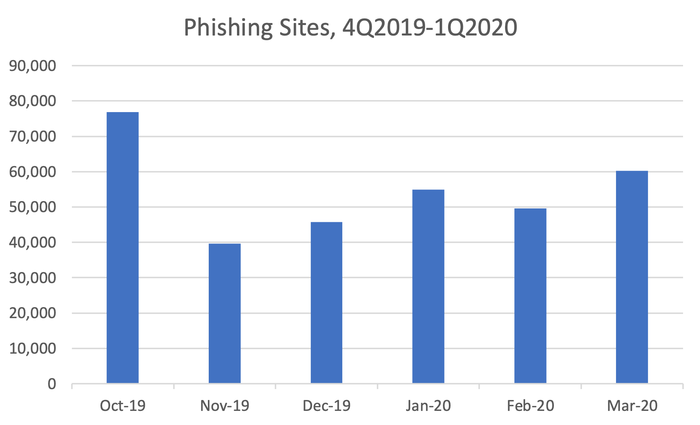

As per the APWG’s Phishing Activity Trends Report, the total number of phishing sites detected in the first quarter of 2020 was 165,772. That was up slightly from the number of 162,155 in the last quarter of 2019.

The primary measure of phishing across the globe is the number of unique phishing websites. This is determined by the unique base URLs of the phishing sites since a single phishing site may be advertised on thousands of customised URLs, all leading to the same attack destination.

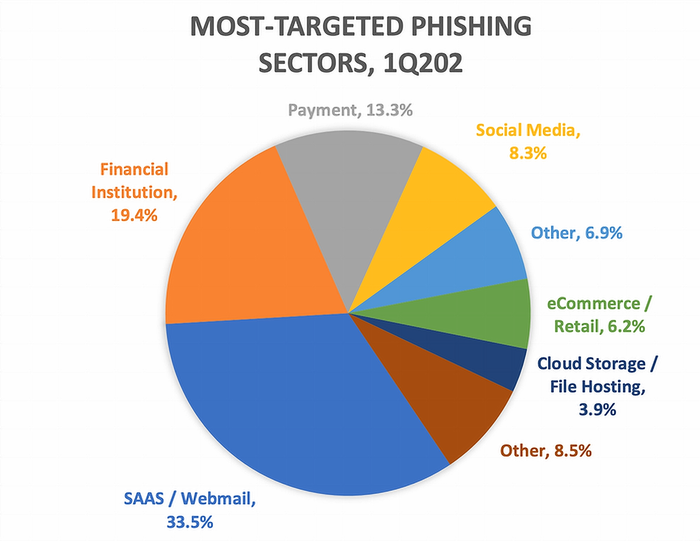

In the same report, APWG published that the financial sector has the noble second place (with 19.4%) on the most targeted phishing sectors list right after the SAAS/Webmail sector (with 33.5%).

Vade Secure collected the 25 most popular brands that are targeted by phishers frequently (in the last quarter of 2019).10 Without the need for completeness, the Phishers’ Favourite Top 10 companies (Q4 2019, Worldwide Edition) are as follows:

- PayPal

- Microsoft

- Netflix

- Bank of America

- CIBC

- Desjardins

- Apple

- Amazon

6.1. Are there Geographical Differences in the Frequency of Phishing Attempts?

Classical opportunistic phishing is usually distributed by bulk e-mail, very similar to spam. In that sense, the distribution is based on huge e-mail lists that do not contain any qualified data like destination country. That means the attackers do not know who they send the messages to. Consequently, it is very hard to conclude to what extent a certain country is “infected” by phishing.

Cybercrime has no geographical borders: phishing servers are most of the time compromised servers in the entire world which are abused to host phishing kits. Taking down only Luxembourgish servers would not help the Luxembourgish users.

7. What is the Situation in the Banking Industry?

As InfoSec mentions, it is not a surprise that the banking industry is one of the top targets of hackers using phishing attacks to breach security.

Banks are offering more and more online services. In parallel, fraud and scam attempts are also evolving and going digital. One of these cyber threats is phishing, which has become dominant in recent years.

7.1. How Is the Banking Industry Targeted?

Phishing has been with us since the ’90s, but the focus of phishing campaigns has been shifted recently. According to a report from Kaspersky Labs, nearly 50% of phishing campaigns attacked individuals and bank customers.

But as banks have improved their fraud prevention measures to protect their most precious assets (their customers), the focus of cybercriminals has also changed targeting high-profile individuals or the banks themselves. Instead of simply relying on blind luck, the phishing scams nowadays target senior executives in spear-fishing or whaling scams.

Just like a private eye, cybercriminals create a detailed profile of their “client”, but in this case, the target is not a missing person or a presumably adulterous spouse, rather a senior executive of one of the banks. The swindler collects all kinds of information about the target person: besides personal information, the favourite watch- or car brands, the preferred yacht club, or even the best-loved local restaurant can be valuable information.

In the next phase of the scam, the swindler elaborates in detail how s/he will approach the target person. The message must be well crafted, detailed, personalised, so the target will not detect anything suspicious. The target should feel comfortable opening the e-mail and clicking on the link in it without even thinking about being deceived.

Once the link is clicked, the chance that the phishing scam becomes successful is much higher: the target has been redirected to a phishing site. This is a fake version of a real site, where the targets feel themselves at home: they have been here several times (maybe this is the website of their favourite restaurant, golf club, car dealership, etc.) so logging in (providing the relevant e-mail and password combination) does not raise any red flags for them.

With that information, the swindler can try logging in other websites which the victim uses frequently. The final aim is to get passwords to bank accounts, or credit card numbers and codes, so the swindler can acquire some money ultimately.

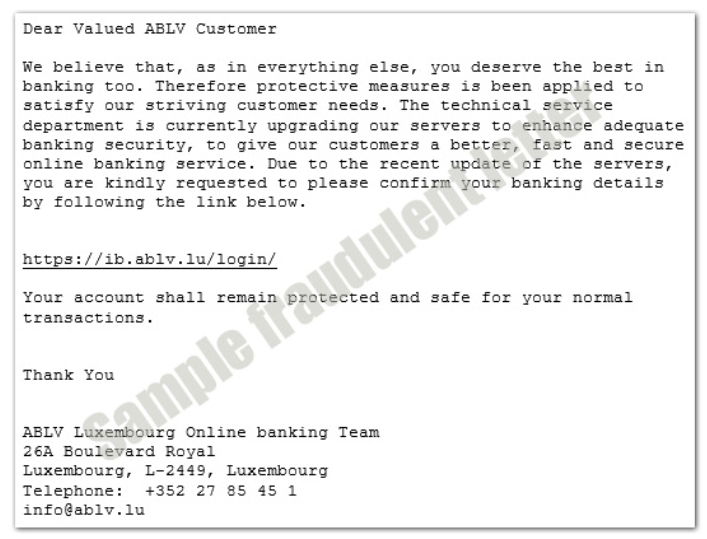

To put this process in the context of phishing scams related to banks, swindlers copy bank logos and lure their victims to fake bank websites where their victims can bite in the phisher’s hook by providing their credentials. This is an example of a phishing e-mail from the ABLV Bank Luxembourg:

But this is just the tip of the iceberg: instead of attacking individuals, sophisticated hacking groups have been increasingly attacking financial institutions recently.

With the information gained from the same above-mentioned senior bank executive, cybercriminals can impersonate them and send an official-looking e-mail to someone else at the same bank who has the power to authorise the transfer of funds, for instance.

Well-executed social engineering techniques are key in this step since the more the swindler knows about the colleagues of the target the better. Knowing the target’s relationship with the colleague approached in this second mail, the processes within the bank to transfer money can be vital in the success of a phishing scam.

And, this is not SCI-FI, as we have several examples of this have happened already: the Belgian bank Crelan lost €70 million ($75.8 million) when a hacker posed as the CEO and convinced someone in the finance department to wire the funds overseas – reported by Cybersprint.

7.2. What Banks Can Do to Fight Against Phishing Scams?

Safeguarding customers’ interests is a top priority for banks. Even though banks are continuously investing resources in the fight against cyber threats and improving their safety protocols, it is often the human element that is the weakest link in detecting the scam, resulting in theft and financial damage.

Banks Educate Their Customers

Various proactive measures are in place to help customers guard against this cybercrime: banks have been proactively educating and alerting their customers by issuing scam alerts and cyber safety tips via multiple channels.

Defending against phishing scams is a joint effort, and banks alone cannot defend their customers if they fail to play their part by safeguarding their passwords and keeping their personal devices and data safe: customer vigilance is critical.

Customers should check with their bank if they receive an SMS or e-mail they suspect to be a phishing attempt. This is especially the case if the SMS or e-mail is unsolicited and asks for their personal or account details.

Banks Must Do Their Part

Besides continuously informing and educating their customers about phishing scams, banks must be relentlessly vigilant and do preventive and protective IT measures against such cyber-attacks.

They can set up “Phishing Indicators”: to create a phishing website, phishers need to register a domain, purchase or transfer ownership of the domain, create and publish new content. The aforementioned steps are all traceable, detectable, so continuous monitoring for such traces can make it possible to take preventive steps even before the phishing site would become alive.

“Easy Solutions” Detect Monitoring Service® identifies and keeps track of malicious cousin domains. In this way, banks can remove sites, profiles and apps imitating their brands before an attack can trick their customers.

Financial institutions should also fight against e-mail spoofing by using the DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance) standard. This protocol confirms that once a spam e-mail fails the authentication check, it will never be delivered to the inbox of the bank employee.

Besides preventive and protective measures, banks should also develop and maintain a phishing attack response process: the incident response team (CSIRT) and the procedure to be followed as well as the documentation and knowledge transfer should be elaborated.

8. What is the “Phishing Landscape” in Luxembourg?

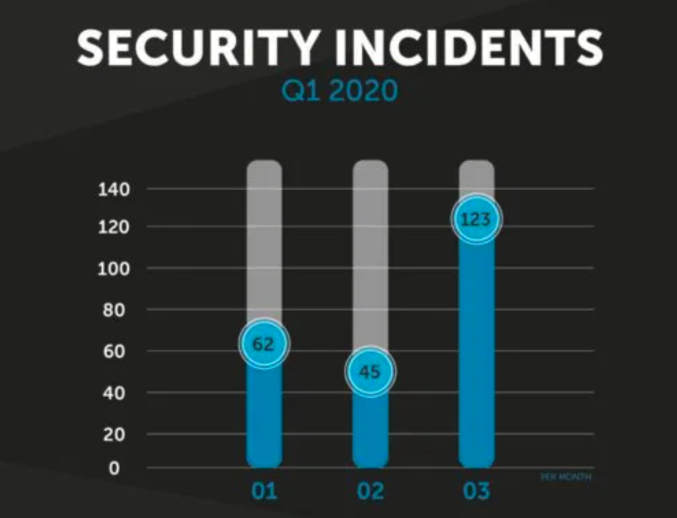

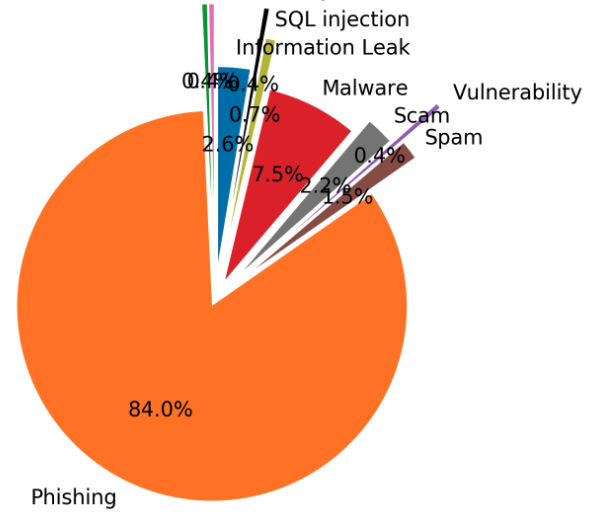

Very recently, the POST Cyberforce Team published an article about the local situation. As can be seen in the graph below, the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown had a significant positive effect on the number of phishing attempts.

“Phishing took a particularly dark turn during the quarter with the presence of multiple campaigns targeting customers of Luxembourg banks in order to steal their login ID and generate fraudulent transactions without the customer’s knowledge.”

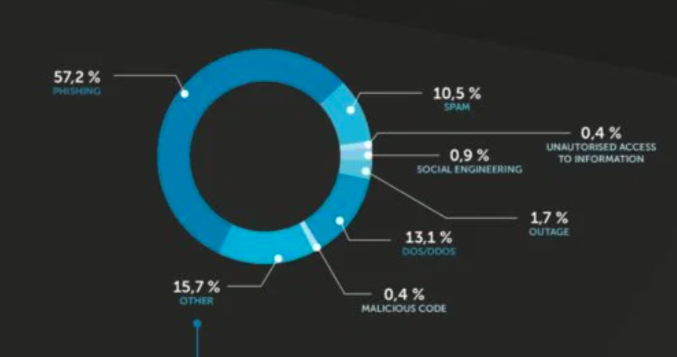

The article also reports that 57.2% of all incidents were phishing:

It is very hard to provide reliable data on phishing attempts. The majority of cases have never been reported, the receiver of such scam e-mails might simply delete those without reporting them.

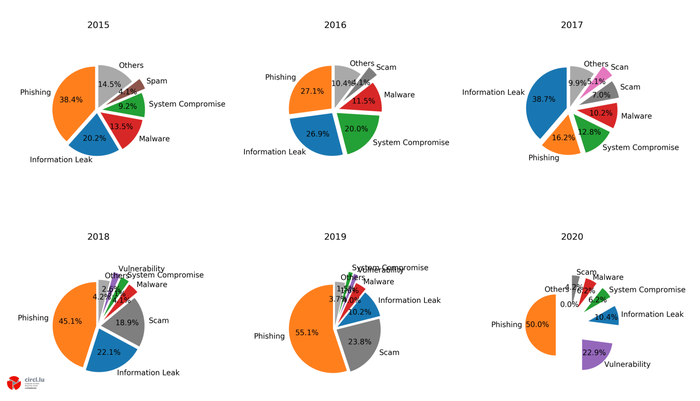

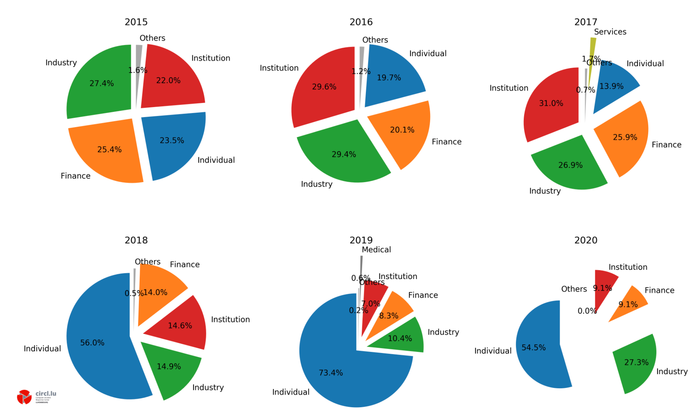

The Computer Incident Response Center (CIRCL) is a government-driven initiative to gather, review and respond to cyber threats and incidents. Below, you can see the percentage distribution of reported incidents at CIRCL in the last five years. As the pie charts show, phishing has always been a dominant threat between 16.2% and 55.1% of all reported incidents between 2015 and 2020.

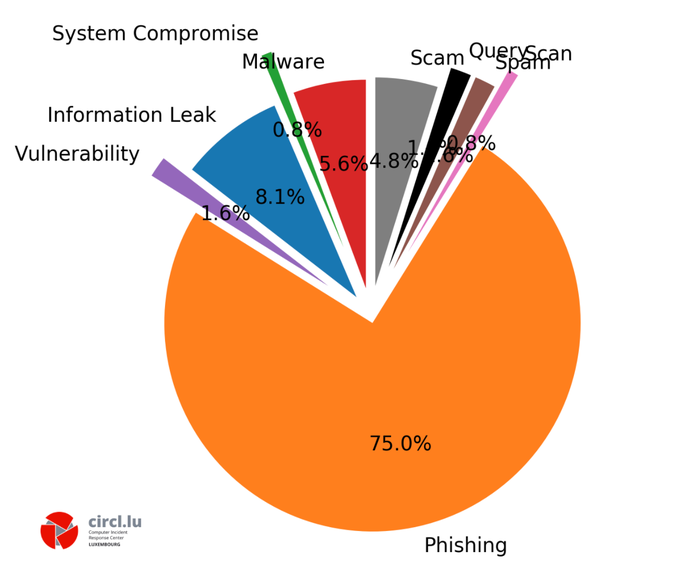

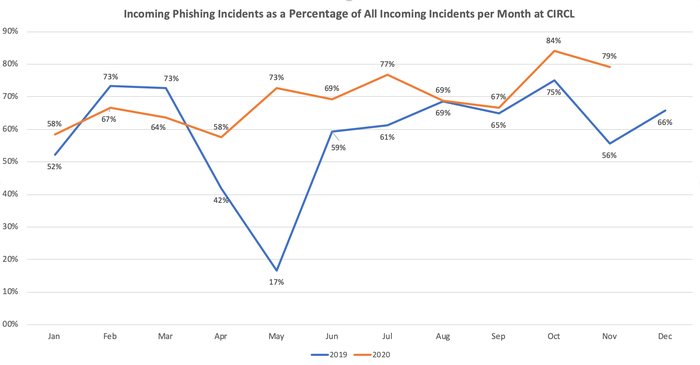

If we take a closer look at the data and check the CIRCL ticket classification distribution, the picture is even more worrisome. In October 2019, three-fourths of all reported incidents were phishing:

The chart below shows the percentage of all incidents received that were phishing since January 2019. The blue curve shows the data for the year 2019, while the orange for the year 2020 in percentage by month.

Since April 2020, the percentage of phishing incidents received by CIRCL has always been higher than in the same month of the previous year. It is also worth mentioning that in October 2020, 84% of all incoming incidents were related to phishing:

The largest discrepancy was in May, with only 17% of all cybersecurity threats received in 2019 being phishing, compared to 73% in May 2020.

The sectoral distribution of cyberattacks between 2015-20 shows that the finance sector has always been a popular target. We can see a downward trend in the numbers of cyberattacks reported in this sector though (from 25.4% in 2015 down to 9.1% in 2020 so far). The upward trend of the “Individual” sector, on the other hand, is very conspicuous: after a small decrease to nearly 14%, a huge peak can be seen in 2019 with a remarkable incident rate of 73.4%.

9. Examples of Recent Phishing Scams

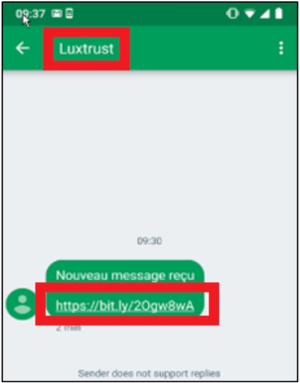

9.1. BIL SMS Phishing Attack

BIL reported that at the end of 2018. Their clients have been targeted by a wave of SMS phishing attacks.

At first, BIL clients have received an SMS that appeared to be from LuxTrust. Normally, you do not receive a bit.ly link from your bank, correct?

To further protect their customers, LuxTrust has implemented a new feature: their users are asked to choose and remember a secret image as an additional security step for online operations. The image chosen by the client appears each time they enter their OTP or their PIN to log in to their online banking space or sign a transaction. This extra step creates an extra barrier to become a victim of a cyber-attack like phishing. LuxTrust has also warned its customers recently against phishing emails.

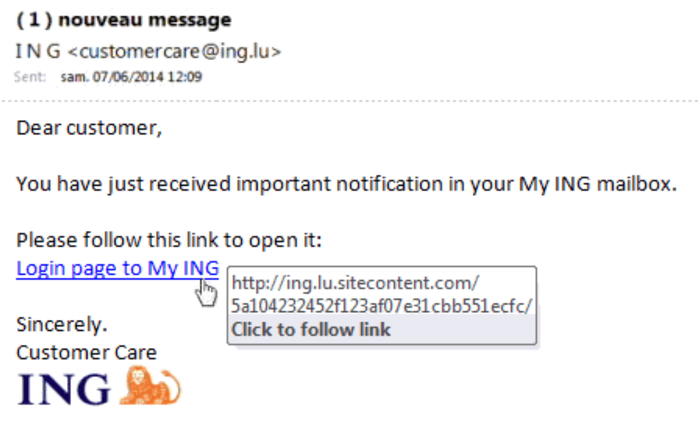

9.2. ING Phishy E-mail

In the following example, ING customers received a phishing e-mail asking to follow a link urgently. The screenshot shows that the link directs its followers to a different site, not the official ING site:

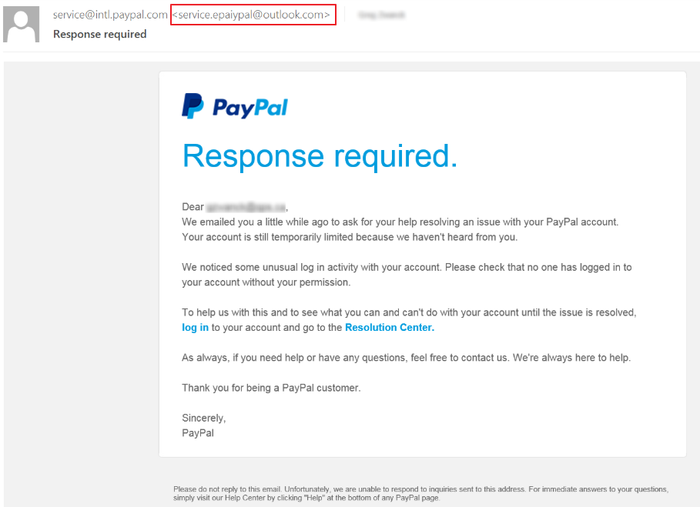

9.3. PayPal Phishy E-mail

Below is a fake PayPal e-mail informing the targets about an “unusual login activity” with their accounts.

A circumspectly fabricated e-mail eerily resembles an original one, but would you respond to a mail that claims itself an official PayPal e-mail but in reality, it is from “service. epaiypal”?

10. Detect and React a Phishing Attack

10.1. What are the Clues of a Phishing Attack

- Messages with misspellings and typos, multiple fonts or oddly-placed accents.

- Messages that claim to have your password attached. You should never receive your password in an attachment.

- Mismatched links. Hover over a link and make sure the link goes to the place shown in the e-mail.

- Messages asking for your personal information.

- Messages claiming that your account will be deleted or blocked unless you take immediate action.

Further clues:

- Any message suggesting the availability of a vaccine or any kind of product supposed to cure Coronavirus is by definition very suspicious.

- Claims to be from a charitable organization is also a common trick used by criminals

- Mails from company HR departments prompting the receiver to reveal login credential must also be handled very carefully.

- Some emails distribute malware. In one version, discovered by KnowBe4 researchers, the author asks for help finding a “cure” for Coronavirus, urging people to download software onto their computers to assist in the effort.

For further information, please consult with the flyer below on Bank Phishing E-mails:

10.2. What Should I Do if Things seem ‘Phishy’?

Be wary of any unusual requests and trust your initial judgement. If a request seems suspicious, do not click on any links or download attachments.

- SPAMBEE: it is a tool that allows you to easily handle suspicious emails and notify experts who will make a complete diagnosis of each transmitted email.

- URLabuse: with this free tool, you can monitor and check the maliciousness of a link.

- Lookyloo: is a tool also developed by CIRCL that gives you a quick overview of a website by scraping it and displaying a tree of domains calling each other.

- MISP: it is a platform for sharing threat indicators, threat intelligence within private and public sectors. MISP users benefit from collaborative knowledge about existing malware or threats.

- SPAMBEE: it is a tool that allows you to easily handle suspicious emails and notify experts who will make a complete diagnosis of each transmitted email. Once processed, these emails will feed a database of senders to ban. This “blacklist” will be shared with all SPAMBEE users. In this way, the anti-spam filter will be enhanced thanks to the participation of each user. SPAMBEE is a joint initiative of BEE SECURE, the CNPD and the Cybersecurity Competence Center Luxembourg (C3).

- URLabuse: CIRCL has developed several services to detect malicious software or suspicious documents. They can monitor links with PasteMining or check the maliciousness of a link with the URLabuse tool. If you receive a suspicious e-mail that claims to be from your bank, call your bank and clarify with a representative of the bank whether the e-mail was sent by them or not. You may certainly forward the e-mail to CIRCL (info@circl.lu), or delete it immediately.

- Lookyloo: is a tool also developed by CIRCL that gives you a quick overview of a website by scraping it and displaying a tree of domains calling each other. The name “Lookyloo” comes from the Urban Dictionary and means “People who just come to look”.

- MISP: another free tool from CIRCL is called MISP (Open Source Threat Intelligence and Sharing Platform). MISP is a platform for sharing threat indicators, threat intelligence within private and public sectors. MISP users benefit from collaborative knowledge about existing malware or threats.

10.3. What Happens When I Report a Phishing Mail?

Using any of the tools mentioned above (SPAMBEE, URLabuse, Lookyloo or MISP), the reported suspicious emails will be sent to CIRCL for analysis and further investigation.

CIRCL is collecting URLs to phishing websites from various sources, including the aforementioned URL Abuse service. These websites are systematically registered, deduplicated and pre-processed: some of these can be processed fully automatically, others need a review of a CIRCL operator. CIRCL tools allow efficient processing and decision-taking whether the reported URL is phishing or not.

Once a ‘phishy’ website is found, its address is investigated and the website owner is to be informed automatically about the phishing website. In this mail CIRCL requests the take-down of the website, which means blocking, removing or otherwise making the website inaccessible to prevent further damage.

At the same time, during this automated process, CIRCL submits the phishing site to its partners, to integrate the phishing address into filter lists like Google Safe Browsing. CIRCL does this dual approach of reporting to filter lists and handing in take-down requests in order to inform the operators about malicious activities, which they are often unaware of.

10.4. How can I stay informed about the phishing threats?

CIRCL help companies sharing threat information through their threat sharing platform MISP. In critical situations, they also inform you via their Twitter account @circl_lu.

Always stay vigilant, think before clicking, and never give up the good hope: you can avoid becoming a victim…

Do not forget:

“The highly vulnerable element that will always be present, no matter how much cybersecurity improves over the years, are humans, and human response to potentially damaging requests for information.”

– Symbol Security, 2019